The testing ground.

A solo traverse in South Westland

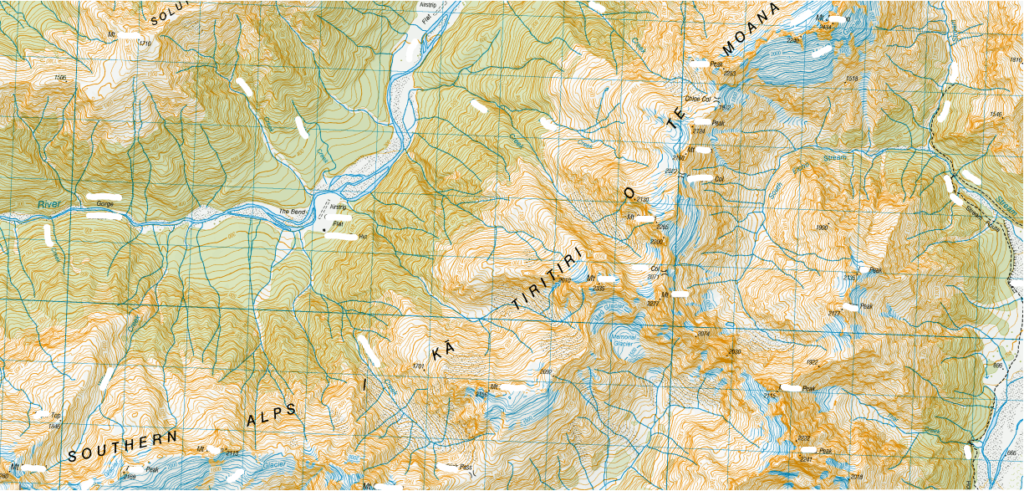

A four part series of an attempt of an East-West traverse of the Southern Alps, from the Hopkins River to the West Coast Highway, encompassing the Landsborough and Karangarua Valleys.

Adventured 6-10 Jan 2017

An unlikely inspiration.

The Landsborough. Epic, wild and remote. Whenever its name is mentioned, a hushed silence falls over the pub. Patrons leave their conversations hanging, unfinished, in the air. They lean in on their barstools, their forgotten beers held halfway to their lips, to hear a real story of adventure.

I have been obsessed with the Landsborough since I was a child, as my Dad spun stories of hunting in this great valley. I wanted to experience the wild country, to have a story that would bring an expectant silence to the pub.

I started planning and researching. I was looking for a route when I found a blog post about a solo tramper. The route he took sounded awesome, and I read on, enthralled. Then, just as the author was right at the heart of this wilderness, he slipped and tumbled off a bluff.

He suffered horrific injuries and his remarkable story of survival went on to feature as an episode of an international television series. Despite the obvious risk, I was still intrigued by the route he had taken. There was no doubt as to the consequence of venturing into this country without the appropriate experience and skill. I examined my competence for weeks, and carefully gathered as much information as I could. An episode of “I Shouldn’t Be Alive ” is a strange place to find inspiration for a trip but with the consequences laid out in unapologetic clarity the challenge was irresistible.

So, in January 2017, I waited for a weather window and set off into the wild country to attempt an East-West traverse, from Ōhau to Fox Glacier. I hoped I wouldn’t end up on TV.

Day 1

Look adventurous!

06 Jan 2017. 0630-ish

“See you on the West Coast, Mum” I said, and hauled on the straps of my pack, swinging it from the tray of the battered farm hilux.

“We’ll see ya” said Mum and grinned. “Oh I need a picture! Go stand over there and look adventurous”

A camera materialised. I went to stand ‘over there’ and tried my best to ‘look adventurous.’

A few more things were said, but most importantly a few things were not said. This miscommunication would cost me time and dignity and I wished I had spent a few more minutes planning for the end of the trip.

I turned and searched for the first track marker. I placed one boot in front of the other. So far so good. Felt pretty easy. Surely I could do that another 118, 000 times.

Cliché heading about beginning, journey of a million steps etc.

The first hour of a long journey is strange. Nerves start to recede and began to be replaced by excitement and the joy of being in the moment.

Thoughts of I’m finally doing it, it feels so good to be started raced through my head, not yet replaced by mid-journey thoughts of:

- One line of a song playing repeatedly for 6 hours straight, and/or

- a random craving for a butter chicken pie.

But I haven’t really started yet I thought. The warmth of the truck lingered in my bones, not yet replaced by the deep chill of the wilderness. There have been no challenges to overcome, and I wasn’t even sweating. These feelings hung over me, and the earth churned beneath my boots as I raced up the lower reaches of the valley, eager to turn steps into kilometres.

The first hut appeared in the distance and gradually grew to fill my vision. My boots thudded on the deck as I stepped in to sign the hut book. A middle-aged couple cuddled on a mattress on the floor, and sat up amongst hastily rustling sleeping bags.

The man gained his composure first. “Morning. Where are you off to so early?”

I smiled, for some reason enjoying the fact that I had already walked an hour and he was still in bed.

“Up. Over the Pass,” I said with unnecessary mystery.

He raised his eyebrows. “Into the Landsborough? It’s big country in there.”

“Lucky I’m a big boy!”

The woman was looking out the window, facing the North Branch. “It looks like it’s clagged in. I hope you’ll be careful.”

I nodded. “Well, I’ll get as far as the hut anyway. If it’s still clagged, I’ll stay the night.”

It doesn’t look good

The North Branch flew by. I was beating the DoC times by hours and feeling good. The scenery was great, my pack was strangely comfortable. If only the weather would behave! Low clouds hung over the mountains at the head of the valley, and it was hard to know what I would be confronted with.

I worked my way up the valley, the track diving in and out of the bush. I was rock hopping in the riverbed when snow covered peaks appeared above the trees. I stood in the riverbed and pondered the shrouded crags, swimming in a current of cloud high above me. Dark tendrils of doubt snaked around the edges of my mind.

Knowing I was close to the next hut, I pushed on.

The forecast for the following days was acceptable. If I got over the pass, I would have good weather in the Landsborough. The situation didn’t look great, certainly far from inviting. Thin wisps of cloud raced along the ridgeline.

How windy was it up there?

This trip was about pushing my limits, testing myself against the unforgiving face of nature. I had to push – but not beyond what was safe. I was travelling solo, which meant I’d already rolled the dice once – I had rolled a three, not too bad but not great. The thing about the New Zealand weather dice is that it never stops rolling. A three could turn to a six, real quick.

I had to make good decisions.

What to do, what to do? When in doubt, make a brew.

The jetboil hissed, the sound bouncing off the walls of the hut. The familiar routine of making a brew cleared my brain.

I weighed the situation carefully in my mind.

The forecast had indicated that the weather would be clearing and I had seen glimpses of the top. Even if it didn’t get better I thought it wouldn’t get much worse. It was a marked route, so as long as I was careful, I would stay on course . I had plenty of warm gear, and emergency shelter.

Into the mist

I started with little trouble and followed a cairned route to the spur I would ascend. With a final look back at the hut, in case I found myself retreating to it in a white out, I stepped onto the face.

This felt like the real beginning of the epic trip I had imagined.

Eager to get over the pass, I storm-climbed the lower flank of the hill. Comforting orange poles poked from the tussock face, marking a semi-formed track. As I neared the cloud line and visibility started to fade, so too did this trail.

That’s OK, I can see where I am on the

The map told me I would hit a bench and sidle to the right, so I was happy enough to keep climbing. The outlines of bluffs loomed above and I wondered if I could pick through them if I wandered off route. It was hard to tell if I climbed into bad weather, or if the weather deteriorated. The wind clutched at me, and snaked its icy fingers down the neck of my jacket. My hood flapped furiously and I squinted up though the driving snow, the track now faded to a thin pressed line weaving between the tussocks.

I reached the bench a short while later and stopped once more to reconsider. Was this still safe? It felt ok, as long as I stayed on route. I took a compass bearing to the pass itself and happy I had some sort of nav check I pressed on. Sparse orange poles appeared intermittently , confirming I was still on track. The wind gathered its ferocious force, and howled across the tops. This was getting bad, but I sensed I was close to the pass. I hoped I was close to the pass. The map seemed to confirm it but the seed of doubt had germinated into nagging worry.

Was I putting myself in a dangerous position? Was I simply pushing further into bad weather and hard country thinking I was close to the pass?

These thoughts festered in my brain as I climbed with stubborn strides. Surely.

The incline levelled and my spirits soared.

The wind whipped across the plateau at the pass. I bent my head and pushed against the freezing gusts. I was elated to be on top, but it was horrible up there. I needed to get off the top, quickly.

Dropping in

A new worry entered my head. What if I dropped into the wrong stream? A quick check of the map told me that unless I managed to climb a 2000m peak nearby, I couldn’t mess this up.

I ran my finger up the pass and stopped at the top. I grinned. My finger sat right in the middle of big bold letters spelling SOUTHERN ALPS/KĀ TIRITIRI O TE MOANA. I was on the boundary of Canterbury and South Westland. The weather seemed appropriately wet.

The ground in my bubble of fog tilted downhill. I checked my compass. Still heading Nor’west. Gradually the hill steepened, and the fog thinned. I descended and step by step the white curtains drew back to reveal the head of an alpine basin.

Happy to be out of the wind, I dropped into the stream and worked my way down it. The clouds above rolled steadily westwards, buffeted by the wind. They cracked open and soaring peaks materialised through the gaps, only for the cloud to fold in again minutes later. These glimpses revealed rugged tussocky faces, streaked with columns of bleak bluffs.

A doe and a flock of Pīwauwau

A flash of tan. I stopped where I was and scanned the ground ahead. Two chamois fed on a small flat beside the stream. Fishing under many layers, I brought my binoculars to the surface. A doe and her kid browsed in the tussock, their summer coats blending to the landscape. I heard a clattering of rocks over my left shoulder and spun to face it. Another chamois sprinted across the stream and up the scree face on the other side. The original doe stood in the classic pose of alarm, head high, neck extended, ears up and nose turned to the breeze. She watched the fleeing chamois yearling for less than 10 seconds before fleeing herself. She crashed across the stream, and charged up the slope. Within a couple of minutes she had climbed high above me, with the speed and agility only chamois possess. Knowing she was about to disappear I lowered the binoculars.

I sat against my pack and enjoyed the feeling of being part of the natural world. I contemplated moving on, but was interrupted by yet another clattering of rocks. The doe was hurtling back down the scree.

What the heck is she doing, she only just ran away?

She came all the way down the hill, and back across the stream. As she arrived back at the flat, I saw her kid standing right where I’d first seen it. The doe had run all that way and her kid hadn’t followed. She led it away, crossed the stream and started up the hill. She turned frequently and checked her kid was following. It skipped along behind her in surges and bumbled into her legs every time she paused on a rock. Her tongue hung out of her mouth and her sides heaved as she climbed. Despite her obvious exhaustion she still climbed faster than any person could have?.

With the excitement all over, I picked myself up out of my scree seat and headed downstream. Only 50m from my seat a faint sound stopped me once more.

Zeet zit zit.

I scanned the rocks around me. A tiny bobbing figure appeared in a pile of tumbled rocks. He stood merrily on a mossy boulder, his creamy chest puffed out from his handsome green jacket.

Zeet zit zit.

Another figure appeared from behind a rock. The hopped amongst the boulder field calling to each other as they searched for tiny insects. I stalked closer and eventually saw four of the little rock wrens.

I watched the flock of tiny fellows for some time. I had never seen pīwauwau before, despite a fair amount of alpine time, and several specific trips to known rock wren hotspots. I stayed with the birds for a while, until my fascination was overcome by the urge to get off the hill before dark.

First view

Moirs Guide North had indicated the best way down was to climb to a small spur before the bush line. This presented me with a magnificent first view of the

The descent through the bush was steep and slippery. My ice axe, which hadn’t been necessary in the snow above, made its first appearance. One hour of screaming ankles later I arrived at the flat, and was very happy to see the brand-new hut on it.

Warm… Too warm.

I listened to the forecast on the mountain radio and cooked a quick dinner.

I was wet to the bone, I decided to see if the fire worked.

Well. Did it what.

The hut’s insulated walls and carefully installed fireplace quickly dried all my gear, roasted me out of my sleeping bag and then out of the hut. I doused the fire, opened the hut door and sat panting at the table in my undies. Half an hour later the temperature dropped enough for me drift to sleep on top of my sleeping bag.

The challenges ahead

My journey had started. Already I had faced challenges, and had crossed the first obstacle. I lay in my bunk, knowing that the biggest challenges were yet to come. There was still 50km of hard country between me and my destination on the West Coast. And then there was the Karangarua Saddle. It sat remote and aloof at the head of the valley. It was a sheer bluff of bleak rock, with only one route over it. It would be the crux of the trip and even though it was still more than a day’s walk upriver, its threat loomed over me.